Rebecca Winthrop and Corinne Graff, both Fellows at the Brookings Institute’s Centre for Universal Education have brought out their report titled “Beyond Madrasas: Assessing the links between Education and Militancy in Pakistan.” The analysis by the authors rests its premise on the emerging body of global data showing a strong connection between education and civil conflict.

Global data has come up with evidence that the lower the enrollment rates at primary and secondary levels on the average, the more likely the risk of conflict erupting in that country. The research then seeks to look at the fact-based evidence drawn from the field in Pakistan to find a link to militancy through educational conditions.

However, despite the presence of large gaps in the empirical research evidence available in Pakistan in this regard, the report draws heavily from a number of sources and studies that have looked at the deteriorating state of Pakistan’s education system since the 1980s and its subsequent consequences to the stability and peaceful co-existence of its populace. Thus, the report highlights the power of education reform as a means of supporting security and stability in Pakistan.

It specifies the areas which should be given priority in guiding policy interventions in the education sector while seeking to create dialogue within Pakistan on the possibility of how best to use education for bringing peace and stability back to Pakistan.

In stating its purpose, the report reveals that a great emphasis was laid on the role of madressahs in being responsible for militancy to the exclusion of other educational factors within Pakistan which could be causes as well. Its findings disclose evidence which absolves madressah education from being a prime culprit in fostering militancy in Pakistan.

The analysis states that except for a few militant madressahs that did promote militancy, by and large madressah education is confined to less than 10 per cent of the school-going population of Pakistan. The prime motive of parents in opting for madressah education is religious instruction and is confined to evening classes rather than a full school day. To quote from the report, “What is often cited by parents is the importance of a religious education for instilling good morals and proper ethics. In the words of one Balochi mother, ‘Islam is a good religion, and we want our children to benefit from all it offers. It is only certain interpretations that give it a bad name.’” Nevertheless, since madressahs are affiliated with different schools of Islamic thought with a narrow pedagogy to indoctrinate, sectarian violence may be an offshoot of the same.

The report examines the implications of key findings that have plagued the state of Pakistan’s education sector in the past 30 years. The picture of the dire state of affairs in the educational sector leaves little to the imagination. Enough reporting has been done by donor agencies and UNESCO in highlighting the deficiencies in education provision. Pakistan comes third after Nigeria and India in the number of children out of school and educationally remains at the bottom of countries in Asia.

With continued terrorism a growing concern in Pakistan, a growing body of research is finding connections between poor education provision and conflicts in countries. Consequently, it is not surprising that the report finds that Pakistanis rank violence and extremism as their top concerns; nine out of 10 see crime and terrorism as the most serious challenge facing their country, and 79 per cent are concerned about the rise of Islamic extremism.

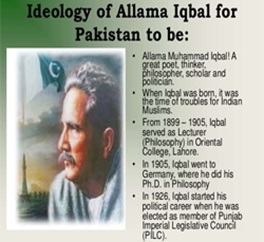

Historically, Pakistan has used its education system to further political gains and foster narrow worldviews. In the 1980s when Pakistan Studies was made compulsory, the books written for the new subjects tampered with historical objectivity and used the contents to give a one-sided and narrow view of the creation of the country. The stance was meant to instill a narrow and fixed view of the events. Not surprisingly, the lacklustre teaching of the subject further aggravated a tendency to rote learn and not question the written content of the books.

Instead of debate and discussion to bring out tendencies for good citizenship, a polemic and dogmatic outlook was formed in vulnerable minds. No wonder in rural settings and far flung areas of the country, the effect must have been manifold. For extremism to take root is easy when pedagogy is confined and restricted. Recent research in the UK on educating against extremism has also found that teachers’ pedagogy plays a crucial role in mitigating extremist worldviews and recommends a range of strategies around listening, open discussion and practicing critical discourse. An “extremist” worldview is one, in the words of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, that does not “allow for a different point of view” and encourages one to “hold your view as being quite exclusive, when you don’t allow for the possibility of difference.”

The Brookings Report underscores five mechanisms which are contributing factors for militancy in Pakistan apart from a couple of militant madressahs. These five mechanisms are as follows and the study finds one salient feature in each:

- Education management for political gain, which highlights important education-sector governance issues that appear to exacerbate core grievances.

- Poor learning and citizenship skills development, which bring issues of education quality into sharp focus illustrating the extent to which key skills are not being cultivated.

- Fostering narrow worldviews, which highlights aspects of curriculum and teaching that appear to support more pro-militant outlooks.

- Lack of relevance of schooling to the marketplace, which demonstrates the dangers associated with education systems that produce graduates with little relevant skills for available jobs.

- An inequitable provision of education, which describes the grievances inflamed by highly inequitable education systems.

No doubt nations have employed education systems in shaping social and political agendas, including identity formation and nation building. In Pakistan’s context, it has been used for narrow political gains at election times and subverting young minds to follow a narrow curriculum based on religious and political agendas. Unfortunately, the deteriorating educational standards since the ’80s contributed to a culture of rote learning in public schools exacerbating the impact of the narrow-minded syllabi on offer. The restricted worldview of the students became vulnerable to ideologies that promoted violence in the name of religion.

The report brings to light a vital factor that in Pakistan’s context aggravate the effects of a narrow curriculum. The teacher’s style of teaching varies widely between public and private schools. Accordingly “Pakistani scholars, such as Pervez Hoodbhoy, argue that many teachers in public schools use rote learning methods, asking students to memorize and recite lessons out loud and copy verbatim in their notebooks lessons written on the blackboard.”

In the context of the above, recent educational reforms under the Musharraf regime improved curriculum and brought in an open door policy in textbook production. Schools now have the choice to select textbooks but the Curriculum Wing has again become an approving body for “passing” textbooks of their choice. These textbooks will be used in public sector schools whose intake is still 70 per cent school-going children in Pakistan. However, there is little impact in the classroom of a broader curriculum and corresponding textbooks utilising new methodology. The report emphasises “an increased focus on teaching pedagogy in addressing the content of what is taught in school is an important way to contribute to a culture of peace in Pakistan.”

This is because the worldviews of students are strongly shaped by teaching. A focus on improving pedagogical approaches, including more interactive strategies that foster critical analysis and questioning, is just as important as revising curricula. The study makes known the views of parents who are forced to send their children to public schools. These parents “have a clear idea of the importance of teachers, versus school buildings or supplies, in providing a high-quality education. The majority of parents surveyed thought that schools without dedicated teachers but with very good infrastructure or free school supplies were “bad” or “very bad.” Close to 80 per cent of parents thought that those schools with poor infrastructure and no free school supplies but with dedicated teachers were “good” or “very good.”

One weak area of the Brookings study is its inadequate depth of research on the language issue that faces Pakistan and continues to radicalise groups of people who do not have access to the English language. The study says, “For example, in 1947 the new national government of Pakistan selected Urdu as its national language and the language of instruction for schooling. In this linguistically diverse country, home to six major linguistic groups and 58 minor ones, this decision was not received positively by all.”

It fails to find the underlying reasons for such a decision that it became the lingua franca of the country and a unifying factor across provinces. It does not mention the social divide caused by the rulers eventually of running two medium of instructional languages — Urdu and English — in schools and furthering the grievances of the have-nots in being denied a language that they feel advances job opportunities.

UNESCO’s many studies bring to light the feasibility of the mother tongue at elementary level to improve literacy in Pakistan. Latest studies also uncover the phenomena of learning the mother tongue proficiently up to grade five, which makes the acquisition of any further language — national, second or third — unproblematic.

Pakistan’s polity has to look deeply at the language issue as a sure way of curbing militant tendencies towards civil conflict suggested by the other five mechanisms that the study has disclosed.

The Brookings study concludes that “Although hard data on education and its links with militancy in Pakistan are limited, a thorough review of the evidence indicates that the education sector and low attainment rates most likely do enhance the risk of support for and direct involvement in militancy. Furthermore, it would be wise to assess the implications for policy, ultimately concluding that the right set of interventions in the education sector could play a significant role in mitigating militancy and promoting security in Pakistan.”

(Dawn)